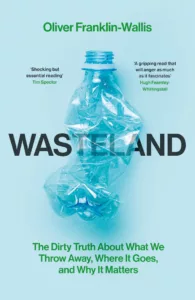

Oliver Franklin-Wallis, Wasteland author: “Our recycling system is broken, but that doesn’t mean we can’t fix it”

Oliver Franklin-Wallis has created something rather remarkable. His book, Wasteland, is an honest assessment of how, globally, we deal with rubbish and waste. It’s the story of what happens to the things we throw away told through the testimony of those who live and work surrounded by other people’s waste.

Wasteland takes the form of a travelogue as we follow Oliver around the world. We experience the Ghazipur landfill in New Delhi, second-hand clothes markets in Ghana and a nuclear facility in Cumbria. Wasteland’s spotlight shines onto the infinitely complex sensitivities and truths behind waste, particularly between the global north and the global south.

To accompany Oliver’s on-the-ground reporting is a history of how we’ve polluted the planet. From ancient Mayan landfills to the Clean Air Act, from Keep Britain Tidy to the circular economy, Oliver weaves a fascinating narrative, making Wasteland a thought-provoking expose of the global waste crisis.

Oliver is an award-winning journalist and author, writing for British GQ, The Guardian, The New York Times and WIRED. His love of technology began in the early 2000s when he worked at a mobile phone repair stall, swapping flat batteries and smashed screens.

Next week, Wasteland is Book of the Week on BBC Radio 4. But you don’t have to wait to hear what Oliver has to say…

Wasteland reminds us that pioneering Sanitarians like Joseph Bazalgette and Edwin Chadwick improved public health by implementing radical waste reforms. Do you think we need modern-day Sanitarians to ease the current crisis?

Absolutely, that’s absolutely spot on. One thing that most fascinated me about diving into the history of waste is the 19th century, particularly around the Great Stink of London and the invention of modern sewerage. We have sewage and clean running water and our grandparent’s grandparents would have lived in a world without it.

The thing that really struck me was the parallels with where we are now, in terms of climate change in the environment. What must it have been like to be in London in 1855, or in Paris and have the river littered with dead bodies, animal muck in the street and not being able to drink clean water without getting cholera.

It’s fascinating that we had Sanitarians, campaigners, politicians and engineers that we’re getting together and making the case for a large-scale intervention. The development of municipal sewers, starting with Joseph Bazalgette, was voted the greatest medical intervention of all time at one point by the British Medical Journal. It was a turning point for humanity.

What fascinates me now is that we can see that we’re in a dire state again. Look at our rivers, they’re all full of sewerage, look at the climate crisis, the amount of waste in the ocean, or even just walking down the road in our hedgerows. It’s clear to me that we are at another environmental tipping point.

Who should step forward to drive the environmental change?

I haven’t yet seen or identified the Edwin Chadwicks of this generation or the Joseph Bazalgettes who are willing to kind of take that consensus, take that activism and channel it into real practical work and practical solutions. It requires lots of political will, unfortunately. In the case of the Great Stink, it literally took it being so foul on the steps of parliament that they were having to drench the curtains in lime to try and mask the smell. It was literally on the politician’s doorsteps and it does concern me that it might take that before we really start to see ambition around the climate crisis and around the waste crisis that we need.

What are the major challenges we face with recycling and the disposal of plastic?

It’s an interesting one and something that I go back and forth on all the time. Fundamentally, the problem with plastics recycling is that most plastics aren’t recycled and they’re not recycled for economic reasons rather than reasons of chemistry or practicality.

Collecting our waste is expensive, sorting it is expensive, washing it and reprocessing it is expensive and virgin plastic is incredibly cheap. The oil industry has got plenty of it sloshing around and they’re betting their future on the growth of virgin plastics, so it’s tremendously difficult for the recycling industry to keep pace. We also have a regulatory environment, which lets people get away with whatever they want when it comes to recycling.

I mention in the book [that] the fundamental way we measure recycling is wrong because we measure it as an input, ie, a truck turns up to the recycling facility, full of bottles and as soon as it drives through the front gate, it’s ticked off as having been recycled. No one’s checking what’s coming out the back gate.

In the UK, when you export waste, there’s no check on the other end to see if it’s been recycled. Once the exporter has accepted it, it’s marked in the ledger as having been recycled. So, it’s just this magic process where it disappears.

How do you think that the recycling industry needs to change?

The first things that we need are legislation, a framework and some rules about what is recycling. How do we measure it? How do we know who’s actually doing it well, versus who’s just trying to pull the wool over our eyes?

There is a move, although I still don’t think it’s gone into effect, for what’s called extended producer responsibility (EPR), that’s the polluter pays principle. That’s so long overdue, this should have been the way that it worked all along. I’m hopeful that it’s going to make a difference.

We’ve seen the offshoring of our waste, plastic waste in particular, decline but we’re still sending hundreds of thousands of tonnes of plastic to other countries to process every year. Our recycling system, as we know it, is broken. That doesn’t mean we can’t fix it. It’s down to consumers to make sure that we keep the pressure on governments and businesses to make change happen.

What four things can our TechFinitive readers do to drive change in their workplace?

The big thing is that waste and the environment shouldn’t be something that belongs to the marketing department. We’ve seen in the last few years that this kind of first wave of responses to things like single-use plastic, and the plastics crisis, have been quite shallow innovations. We saw people switching very quickly to compostable plastics without acknowledging that we don’t have compostable plastic collections. A lot of consumers don’t understand that doesn’t mean that you can compost them in the garden, they need a commercial high heat high-pressure composting facility, of which there are relatively few. A lot of the time the compostable plastics we were embracing were just being burned.

The second thing is that if you make things, design them with the end of use in mind. That doesn’t just mean circularity, using recycled or recyclable products, but making things repairable, and interchangeable and making sure that components can be swapped out to last as long as possible. We’ve seen some interesting steps in the clothing industry. There’s a Swedish kids’ ware brand and they did a very small thing. They have kid’s name labels in the back of their clothing and they added extra lines, so now you can cross out one name and put an extra kid’s name in it. These kinds of cues tell people that products are meant to last longer, and you can pass them on. It acts as a tacit instruction to the consumer.

Also, don’t say one thing publicly and then have your lobbying department say the opposite, in private. We’ve seen that a lot in the last few years as companies grapple with their waste footprint. Often they are public greenwashing and then in private, going the other way.

The other thing is helping customers understand what they can do. One of the fundamental problems with the recycling industry is that it’s incredibly opaque. Nobody really understands the labelling. Nobody knows whether their stuff is being recycled or not. As we are now entering a world where different business models are becoming more acceptable, things like renting, reuse and resale, help customers with, “I’ve done with my laptop, how do I make sure that this goes to someone who needs it instead of into a gigantic electronics blender”.

Companies have a real role to play and I can’t think of very many that have stepped up to the level that we need. Whatever your businesses, whether you’re making clothing or food or electronics or whatever, you can bring customers on the journey with you, because it’s not always as simple for them. The real tragedy at the heart of this story is that everyone you speak to is sitting there, slavishly washing their yoghurt pots and rinsing out their crisp packets, hoping that they’re going to be recycled and they end up in a ditch somewhere in Malaysia. We need to fix the system.

Finally, have you any advice to spot, or avoid, greenwashing within ESG and sustainability reports?

The big one for me in the tech world at the moment is the idea of ocean plastic. You see all of these companies touting materials made of ocean plastic. Then you read the fine print and it’s actually prevented ocean plastic, which the industry definition of is plastic collected within 50 kilometres of a river or sea in the Global South. It’s a staggeringly large landmass with billions of people living within that definition. It is an insane thing to be calling that ocean plastic and it really does down the work of companies like The Ocean Cleanup that are genuinely fishing plastic out of the ocean.

Think about it logically. These things [genuine ocean plastics] have been swirling around in the Pacific Ocean, they’re photo degraded, they’re covered in sea life, they’ve got kelp and things living on them. This isn’t pure PET that’s coming from a bottle bank, so the idea that you’re going to turn it into beautiful or desirable tech products is nonsense. I urge people, and I guess part of this book is to get people to think a little bit more deeply about, some of those solutions.

We have a terrible habit of the first line of solutions to any problem being the shallowest and the simplest. Oh, you’re buying too much stuff, buy this thing instead, when actually we don’t need to buy anything at all. Rather than buying a refillable plastic coffee cup, just have a coffee in a ceramic cup at the coffee shop. Sometimes there are simpler solutions that we already have in front of us.

Everyone wants to do their best for the planet, everyone wants to cut down on their waste footprint. Unfortunately, there is a small group of people who see that as an opportunity to make money and we end up with solutions that are only skin deep.

Waste is a global problem. There’s a reason I spent time in India, Ghana and all over the place reporting this book. Quite often the worse outcomes are on the poorest and most marginalised people in the world. When I see companies say, “Oh, we’ve got ocean plastic” or “we’ve got prevented ocean plastic”, I know there is a family picking that up on a beach somewhere in the Global South, and they are getting paid pennies per day. I’ve seen these people, I’ve met these people.

Now there’s this kind of creeping and somewhat pernicious idea of plastic offsets where you can produce virgin plastic, but pay someone in the Global South for it. That money doesn’t end up in the hands of waste pickers. It isn’t helping elevate their conditions, it’s being taken out by marketing agencies and middlemen who are doing it for themselves.

Whatever the solutions are, they’ve got to make sure that the people actually affected, the people actually dealing with our waste, holding it in their hands, are the ones getting help. I just hope that whatever solutions we come up with, we can make sure that it’s better for everyone.

Related coverage on sustainability

- Is Logitech a green and sustainable company?

- Five simple steps to make your business IT more sustainable

NEXT UP

Andrew Kay, Director of Systems Engineering APJ at Illumio: “The most worrying development with ransomware is that it has evolved from simply stealing data to impacting IT availability”

Andrew Kay, Director of Systems Engineering APJ at Illumio, has 20 years’ experience helping organisations strengthen their cyber resilience. We interview him as part of our Threats series on cybersecurity.

The imperative of making a career in the data centre industry attractive

Adelle Desouza addresses the problem of an ageing workforce in the data centre industry as well as how to make it an attractive career for new generations

I don’t care who hacked the Ministry of Defence, I do care how they did it

We may never know who hacked the Ministry of Defence, says Davey Winder, but who cares? It’s how they did it that has real-life implications